|

Rural areas are neglected by the police. Well, this is what residents in rural areas think and tell the police all the time. The challenges of spreading a police presence very thinly across wide areas is a major headache to the neighbourhood policing team. The dogma that visible policing is what works means that police forces struggle to be seen all over the place, performing the dual role of reassuring the police that they exist, and are friendly, whilst at the same time attempting to 'see off' the baddies.

When police officers look at crime rates data, they understand that there is very little crime in rural areas, and compared to town centres and 'night time economy' areas (pub and club land, for mere mortals like me), rural areas are extremely sleepy. But, a simple division of crime rate into the population of any given rural district soon demonstrates that the amount of crime per head of population is usually about the same as a town or city centre. If one factors in the harm indexes that help us to understand that all crime is not of exactly the same value, and if we factor in the vulnerability of a rural population in terms of deprivation and remoteness, rural areas 'outperform' cities in many respects. So in chasing after 'bulk' crime stats, police commanders are missing the point. Those commanders who do 'get it', however, ask the question; how do we do intensive engagement when the communities we are working in are 'extensive', i.e. widely and thinly spread? Surely the community is so widespread that Intensive Engagement is impossible? It's relatively simple to see that intensively engaging with a small housing estate, or a street corner micro-location will still have plenty of people interested or motivated to get involved, but a vast empty rural area is a whole different game. The challenge here is to shift away from thinking of a community as a geographical entity, to thinking of it in 'social capital' terms. We have to think not in terms of street corners, or housing estates, but intangible links between people who might be geographical dispersed and remote. When we think of 'community' as a series of invisible links between people, then we don't need to be quite so constrained to consider the physical environment. Let's take catalytical convertor theft as an example. A PCSO reported to me that she had been tasked with 'solving' catalytic convertor theft on a rural beat. A few dozen convertors had been removed from farm vehicles but it would take an hour to drive from one incident to the next. The PCSO was scratching her head at the challenge of intensively engaging over that distance! But let's think of this rural community as a series of intangible links. Who are the vehicle owners most likely to contact when their catalytic convertor has been pinched? They will phone their garage to get it replaced and their insurers to get it paid for. Who are the most highly connected and highly capable people in this community to start a working group with? The garage owners and insurers. Sure, their self-interest might be to increase catalytic convertor theft to increase their business, but the one's who want to foster good relations with their customers would be the better starting point. Bringing insurers and garage owners together with other teams, like the National Farmers Union and the Motor Manufacturers Associations, is what is known as building a 'team of teams'. Tim

2 Comments

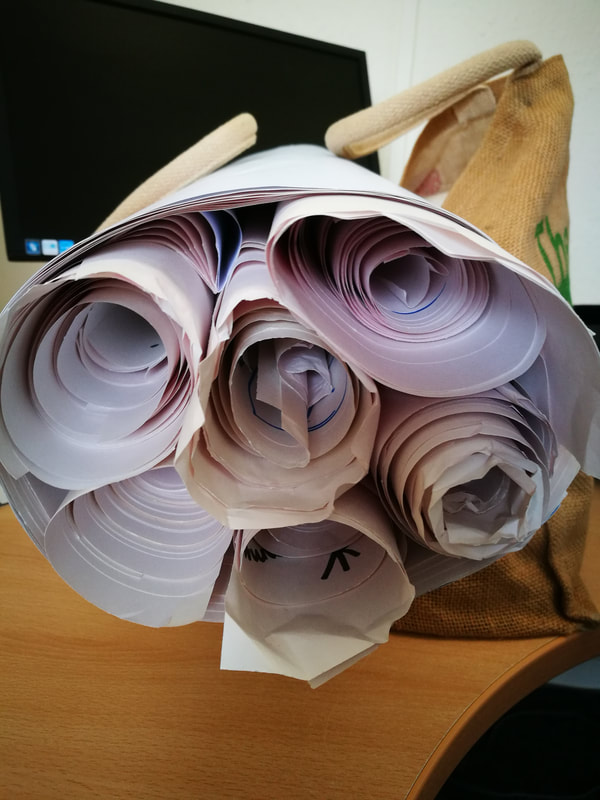

Teaching 'rich pictures'As part of my ongoing university teaching practice, I am teaching over 200+ undergraduates how to undertake an investigation into a new and complex 'problem situation', in their case, that of student food poverty. The process of making sense of their investigation in to to create potential solutions uses the core 'technique' in Intensive Engagement- that of the 'rich picture'.

It is really difficult to teach as a technique because most students (undergraduates and mature students) struggle with the idea of 'drawing a picture' to represent what is going on inside their heads. But as they begin to warm up to the idea, they begin to see the concepts and ideas, the fruits of their research, being sorted out before their eyes as they talk with each other and scribble on a flipchart pad. One student mentioned the other day that it was quite cathartic. He didn't use that word, but he expressed it as therapy. Not only was he making sense of the challenging topic of student food poverty, he was also expressing in an unstructured way, his own understanding of his own student life. He was beginning to appreciate its complexity, the numerous demands on his attention and effort that he had never encountered before. He was able to face this complexity in a constructive manner using the rich picturing, however, because he was doing the structuring, he was completing the links. When we are using a rich picturing technique with community members in neighbourhood policing, we need to remain aware that the picture is not just a representation of the challenging social/crime problem that the team are tackling, but also an unformed representation of the messiness inside our heads. It makes people quite vulnerable to express themselves in this way, but we learn a huge amount about the dynamics of the problem situation. |

ArchivesCategories |

Home

COMPANY REGISTRATION No: 11263857 VAT Number. 291 0707 12.

REGISTERED OFFICE: 13 The Courtyard, Timothy’s Bridge Road, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, CV37 9NP

Equality, Diversity and Safeguarding Policies

REGISTERED OFFICE: 13 The Courtyard, Timothy’s Bridge Road, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, CV37 9NP

Equality, Diversity and Safeguarding Policies

Copyright © 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed